"TIME IS NO LONGER THE SAME"

Time plays tricks on us. When we are waiting for someone, minutes seem like hours, but when we are busy, hours seem like minutes. The summers of our childhood were endless, and today they have not even begun and are already ending. But what is it that expands and compresses time for us? What changes our perception of its length? Zoltán Nádasdy and his fellow researchers tried to answer this question with a simple experiment.

The experiment was originally a university project carried out in the 1980s by Zoltán Nádasdy, then a psychology student at ELTE, and his classmates. Although they found an interesting correlation, the results were not published. In the past two years, Nádasdy's PhD student Sandra Stojić, who has since conducted significant research at ELTE, and her colleague Vanja Topić from the University of Mostar, have repeated the old experiment after methodological refinements, and the results not only confirmed the previously found correlation but also added new data. Their paper, recently published in Springer-Nature Scientific Reports, has in many ways repaid an old debt.

The experiment is very simple and can be done at home. Let's show preschool children two videos of the same length (say, one minute each) (for example, from their favorite cartoon). One should be eventful and the other boring. After the second video has been played, let's ask them which one they think was longer. More than two-thirds of the children will answer that the eventful was longer. Repeat the same experiment with adults, with the same two cartoon clips or anything else, and you will get the opposite answer: for more than three-quarters of adults, the boring movie segment seems longer.

So at some point between preschool and adulthood, the timing shifts.

To see if this shift really happens, the researchers also tested a third age group, 9-10 year olds, and found that they were between preschoolers and adults in terms of their perception of durations, a bit like adults. The researchers added another task to the experiment: the differences in duration between the three groups were also expressed by spreading the arms. But the instructions did not say whether this movement should be horizontal or vertical. Nevertheless, more than 90% of the adults expressed the durations with horizontal arm spacing, while half of the kindergarten children made a horizontal movement and half a vertical movement.

To understand what this is about, the researchers reasoned, we need to look at how estimating duration differs from, say, estimating geometric length. Durations are not mapped in our senses in the same way as brightness, loudness or length. We can see the difference in the length of two lines when they appear simultaneously next to each other, we can compare the durations of two events when they occur simultaneously before our eyes, but

we can only compare successive events by using our memory

- But memory can be tricky.

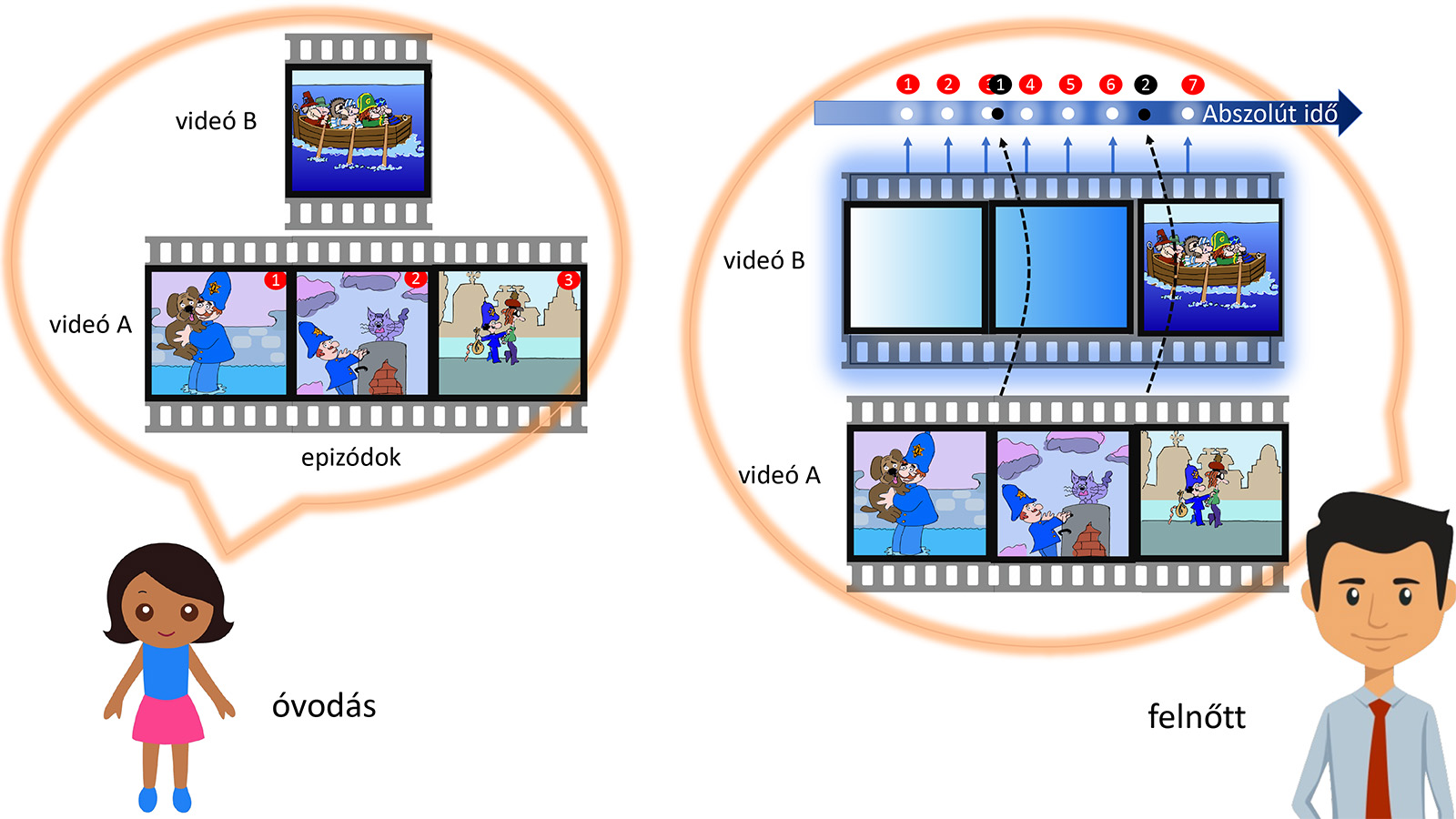

Heuristics was introduced into the lexicon of psychology by Amos Tversky and Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman. They are strategies that we use when we are uncertain and have limited information. In such cases, we invoke a rule that is not exactly what we are looking for, but can give us a result close enough to make a quick and efficient decision. Estimating durations is exactly such a case, and preschool children apply the representativeness heuristic "which one could I tell you more about" to this task. Much about the eventful and little about the boring. So the eventful one was certainly longer, the child argues logically (see left side of the accompanying illustration).

However, children are introduced to the concept of absolute (clock) time at school from the age of 6-7. The clock is a tool that gives them all the information they need to make the right decisions. From then on, their lives are pervaded by time, which is absolute, unstoppable, constantly passing, regardless of where we are, whether we are paying attention to it, whether we can sense it or not. A 10-year-old child already knows that time passes while he sleeps, and he knows that when his 45-minute lesson ends, his brother's lesson ends in another classroom with another teacher, because they are on the same absolute and synchronised time axis, which, incidentally, can be measured to the nearest hour. For the 4-5 year old, this is not yet clear.

If we already understand the absolute time, but do not have a clock to measure the duration of, for example, two videos, we rely on another sampling heuristic. How does this work? We look at absolute time at age 10, but also as adults, as a continuous flow of events, like an imaginary river. Whenever we think about time, we are actually looking around to check if things are in motion, and if they are, it reinforces our experience of absolute time.

Every such moment is a sampling, during which we make sure that time passes.

We rely on these patterns of experience of time taken from absolute time when comparing durations - this is the heuristic we use (see the accompanying illustration, right).

If you're watching a boring film, and your attention is not occupied, you sample absolute time at roughly even intervals: more time over a longer period. But if the film is exciting and keeps our attention, we can barely sample enough to keep from losing track. So when the researchers asked adults and school-age children which of the two films was the longer, they looked back at the two videos, compared the number of time experiences they had during their viewing, and where they found more, they considered it longer. (This is never a conscious process, of course, and is subject to a number of biasing factors, including attention, memory, stress and other factors.)

The experiment pointed out that whatever internal clocks the brain may have, as metronomes can fire neurons at regular intervals, if there is no homunculus in our heads counting the beats, there will be no time estimate. The result is also a great example of how the biological and cognitive levels diverge during development: while biological maturation monotonically improves function, cognitive maturation can take big leaps and even go against previous beliefs.

It is increasingly clear that our brains not only enable us to understand nature, but also set the limits of that understanding. And while we can't stop time, we can at least come closer to understanding how it reorganises and distorts our memories and consciousness. Research has taken a step forward in this process.

Source: elte.hu